Crisis Leadership

“What does it mean to say, “The situation is dynamic”? I think it means we

have no idea what’s going to happen next and that’s just the way it is.”

Margaret. J. Wheatley (2017). Who Do We Choose To Be? Facing Reality, Claiming Leadership, Restoring Sanity. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. Oakland, California. p. 230.

It would be difficult for someone to be alive on this planet in April 2020 and not have heard of the Corona Virus or COVID-19 as the World Health Organization has named it, or that it has declared COVID-19 a Pandemic. This, of course, brings a raft of challenges and potentially opportunities with it as well.

Perhaps the biggest challenge the COVID-19 Pandemic brings is how to lead in a crisis, in which the ground appears to change by the hour and in some instances by the minute. Whilst crisis leadership is usually required because of the uncertainty that has emerged, crisis leadership because of a Pandemic is somewhat different. Crisis leadership during uncertainty usually has some pillars of certainty embedded within it. For example, the sudden death of a colleague will bring a period of upheaval and uncertainty to the workplace and will create a scenario often referred to as a ‘critical incident’. The leaders in this instance are aware of the start date of the ‘critical incident’ and would in their planning be able to ‘guestimate’ an end date of the ‘critical incident’ for most staff members. Likewise, there are processes and procedures that will need to occur that also brings some useful guideposts for the leaders involved in the leadership of the ‘critical incident’. In leadership through a Pandemic though, many of these processes and procedures evaporate and even planning for an end date becomes problematic. To add to the complexity of the situation, the research suggests that in addition to a ‘Business Continuity plan’, a large organization, such as a government agency, should also have a standing ‘Pandemic plan’ and a ‘Recovery plan’. These plans are fraught with difficulties, as it is hard to plan for the unknown. Ultimately, they become an exercise in imagining the absolute ‘worst-case scenario’ and decide the required responses and then step down the responses if the situation isn’t that bad.

So, Margaret Wheatley, in the opening quote to this article, is spot on. The rhetoric from our leaders, including our political leaders, tends to reveal that we have little, if any, idea of what is going to happen next and that is simply the way it is! Any leader that suggests otherwise, is probably playing with the truth.

In an earlier work, Margaret Wheatley noted:

“The world is far more sensitive than we had ever dreamed. We may harbor the hope that we will regain predictability as soon as we can learn how to account for all variables…But in fact, these desires for mastery and prediction can never be satisfied in this nonlinear world. We would do better to abandon that search entirely. In nonlinear systems, iteration helps small differences grow into powerful and unpredictable effects. In complex ways that no model will ever capture, the system feeds back on itself, magnifying slight variances, communicating throughout its networks, becoming disturbed and unstable—and prohibiting prediction, ever.”

Margaret. J. Wheatley (2006). Leadership and the New Science: Discovering Order in a Chaotic World (Third Edition). Berrett-Koehler Publishers. Oakland, California. p. 122-123.

In the 1990s and beyond, scholars such as Margaret Wheatley, Michael Waldrop, and James Gleick, began work on an emerging area of study often referred to as Complexity or Complexity and Chaos. As a writer, I published two papers on Complexity and Chaos in the late 1990s: Managing the Entropic Organization (1997) and Managing from the Edge, Working from the Centre: Organizations, Complexity and the Search for Meaning (1998).

In terms of our current woes, Complexity and Chaos is certainly one lens, through which we should be looking at the world. This lens starts from the notion that the world is naturally chaotic and that humans put order onto the world, so that life can become manageable. This has been extremely beneficial for humankind but can lead to a false sense of security. If you apply the lens that the world is chaotic, then you become more open to what is possible and oddly enough, you may even find patterns within the chaos that can help you lead. This task is best done with a team that is led by a Pandemic Coordinator. COVID-19 has, after all, changed almost every aspect of life and plays by its own rules. It has forced us to consider: how we engage with our job, how we engage with the world of business and commerce, how it has impacted on personal freedoms, including freedom of religion, how it might impact on our health and wellbeing, beyond contracting COVID-19?

For an employer, COVID-19 has given them much to think about.

- How do I allow my employees to work from home?

- Do we have access to the needed technology to support my employees from working from home?

- What professional learning will my employees need to work in this virtual work environment?

- What will these changed working conditions do to our budget?

- Do we have adequate insurance for our workers, now that they are working from home?

- At what point will employees be ‘stood down’ without pay and the business close until COVID-19 ends?

- How can we meet customer expectations when our physical locations are closed or working to a very modified timetable and with skeleton staff?

- What safety issues do employers need to consider?

An issue here and currently not stated in the literature or rhetoric, is how you balance trust with accountability? For a leader, it is natural to want assurances that your staff will maintain their level of productivity whilst working from home, rather than from the office. The reality is that for some, their productivity might actually increase.

In the context of the current Pandemic, it is worth reflecting on the ‘big rock’ issues that organizations will likely be confronting. Some of them will be obvious. For example, if people are living in an area of lockdown and are prohibited from traveling from home to most places, then soon those places will close, even if only for the Pandemic. In Australia, on one Thursday afternoon, 4 major retail companies that were the parent companies to some big brand names, closed their doors for the duration of the Pandemic. The net result, 30,000 retail employees were ‘stood down’ in one afternoon. This forced the Australian Government, to provide an assistance package to those ‘stood down’. In the Employment Laws in Australia, a person who is ‘stood down’ is still on the books of the company as an employee. This means that they would normally be ineligible for unemployment benefits or government assistance. The economy cannot sustain large groups being unpaid for an undefined period of time. To date, the Australian Government has committed to a number of large scale assistance plans for various groups in Australia affected by COVID-19. Currently, that totals over 16% of Australian GDP.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention has a Pandemic Planning Checklist that businesses may find useful. The important thing for leaders of organizations, including Government agencies, to know, is that the internet gives them access to a wealth of resources, provided by experts, that will help to guide them through the planning process for both a Pandemic plan and the broader Business Continuity plan and the Recovery plan.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the following ‘Big Rock Issues’ for leaders to plan around when responding to a Pandemic crisis.

- Plan for the impact of a pandemic on your employees and customers

- Establish policies to be implemented during a pandemic

- Allocate resources to protect your employees and customers during a pandemic

- Communicate to and educate your employees

- Coordinate with external organizations and help your community

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (2005). Business Pandemic Influenza Planning Checklist.

Perhaps the biggest challenge the Covid-19 Pandemic brings is how to lead in a crisis, in which the ground appears to change by the hour and in some instances by the minute.

Sitting in the background of the Pandemic are two issues that are silent but could become problematic further down the track, Trust and Belonging.

As a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute (Great Britain and Ireland), I would posit this simple Anthropology of the current workplace and the COVID-19 Pandemic. I do so, to address the issue of belonging.

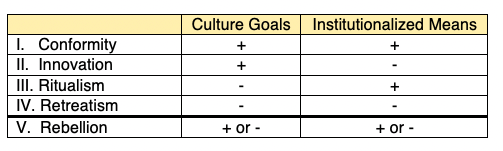

From work, the average person finds dignity and gains a sense of belonging. When you go to a function, it is not uncommon for people when being introduced, to be asked: “what do you do for a living?” Right or wrong, this question assumes that you are at work and that means that you belong to an employer or run your own business. Consider that through work you will often find like-minded people and become good friends with them, inside and outside of work. This is very common in professions such as teaching and nursing. Also, consider that the employee is financially dependent on the employer for their income and money. Further, consider that those looking for promotion to the senior ranks will often be involved in the polity of the organization. In short, there are multiple ties that ‘bonds’ a person to the organization. When the organization is no longer available or easily accessible to them, in order to meet needs, these bonds start to dissolve. For a person who lives by themselves with a limited social circle or the person who has assimilated their role in the organization into their self-concept, a rupture of these multiple bonds will start to occur. Whilst Merton’s Strain / Adaptation Theory (Models of Deviance) has always generated debate within the fields of Sociology and Anthropology when it is applied to our Anthropology of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Workplace, we start to see the possibility of Retreatism occurring. According to Merton, there are “five logically possible, alternative modes of adjustment or adaptation by individuals within the culture-bearing society or group. These are schematically presented in the following table, where (+) signifies “acceptance,” (-) signifies “elimination” and (?) signifies ‘rejection and substitution of new goals and standards’.”

Robert K. Merton (1938). Social Structure and Anomie.

Source: American Sociological Review, Vol. 3, No. 5 (Oct. 1938), pp. 672-682 Published by: American Sociological Association See p. 676.

Within the current set of Pandemic generated circumstances, the other 4 modes of adaptation, including the Rebellion mode, all find something with which to attach, adjust or adapt to. ‘Retreatism’ represents the person who finds they have no goals to achieve and no means to achieve a goal, should they have one. For this person, any reasonable employer would have to be concerned about their well-being and psychological safety. Though they might be working from home, they are still in your employment and that, of course, brings responsibilities under most Work, Health and Safety Laws for the workplace. Thankfully, the solution is not that difficult.

A simple way to attend to the issue of ‘belonging’ is for members of the leadership team or the leader themselves, touching base with each member of the team by phone or by video conferencing using Zoom, Skype, Microsoft Teams or something similar. One model would be a ‘Team Video Conference’ on Monday and maybe Thursday. At this briefing, team goals are reiterated or redefined, responsibility for immediate projects are given and the team have an opportunity to feedback from what they have been doing and raise issues. On Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday, a simple 5-minute phone call to each member of the team could be made. This would be more along the lines of: “How are you going with those targets? Are there resources you still need to advance the progress on those agenda items?” Ideally, the leader and the 2-i-C could share the phone calls if it is a large team. This ensures that people do not feel isolated, their work is valued and they have the ability to contribute, either through the team video conference or via the individual phone call. It is important they understand that they still belong to the organization and that you trust their professionalism.

Harvard Professor, Nancy Koehn, writing in her article “Real Leaders are Forged in Crisis” in the Harvard Business Review (April 2020), noted something similar. Professor Koen contends that the test of real leadership is found in how a crisis such as COVID-19 is handled. “Leaders become “real” when they practice a few key behaviors that gird and inspire people through difficult times.” (Nancy Koehn. (2020) Real Leaders are Forged in Crisis.

Professor Nancy Koen articulates the following behaviors that leaders need to exhibit through a crisis such as a Pandemic:

Acknowledge people’s fears, then encourage resolve

Here Koen cites leaders such as President Franklin D Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill as leaders that were adept with the use of words followed by action, to address the fears of the people and bring about a resolution.

Give people a role and purpose

“Real leaders charge individuals to act in service of the broader community. They give people jobs to do.” Here Koen cites leaders such as President Abraham Lincoln and Rev. Martin Luther King Jr as good exemplars of this practice in leadership.

Emphasize experimentation and learning

“To successfully navigate crisis, strong leaders quickly get comfortable with widespread ambiguity and chaos, recognizing that they do not have a crisis playbook. Instead, they commit themselves and their followers to navigate point-to-point through the turbulence, adjusting, improvising, and re-directing as the situation changes and new information emerges. Courageous leaders also understand they will make mistakes along the way and they will have to pivot quickly as this happens, learning as they go.”

Tend to energy and emotion — yours and theirs

“Crises take a toll on all of us. They are exhausting and can lead to burnout…Thus, one critical function of leadership during intense turbulence is to keep your finger on the pulse of your people’s energy and emotions and respond as needed.” This goes to the heart of the Anthropology of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the issue of Trust and Belonging. Employee Access Schemes to ‘Mental Health Care’ professionals will be critical at this time.

Next, model the behavior you want to see

“This means using your body language, words, and actions to signal we are moving forward with conviction and courage. It means regularly taking the (figurative) temperature of your team — How are they doing? How are they feeling? What do they need? — so that its members begin to do the same for each other. Indicate that you are taking the time to rest and recharge and encourage your employees to do the same.”

Nancy Koehn. (2020) Real Leaders are Forged in Crisis. https://hbr.org/2020/04/real-leaders-are-forged-in-crisis

On the flip side, through COVID-19, the world stands on the precipice of some remarkable opportunities. With parents having to home-school their children in various jurisdictions, including Australia, whilst working themselves, a healthy appreciation of the diverse skillset of professional teachers in the 21st Century has emerged. No doubt school authorities will look at what was achieved during the COVID-19 Pandemic and keep that which has proven to be ‘best practice’. No doubt the same thing is occurring in the health care profession, especially medicine and nursing. This, of course, has raised the specter of improved funding for medical research as well. The Anthropology of the situation reveals that the economies of the world are at great risk. In many jurisdictions, including countries such as Australia and New Zealand, their Governments are trying to ensure a soft landing for their economy post-Covid-19. The hope is that when economies come out of the COVID-19 Pandemic, there will be jobs for people to go back to immediately. This again addresses the major issue of people’s sense of belonging and their sense of human dignity. We have much to endure and much to learn!

“The dogmas of the quiet past, are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise — with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.”

Abraham Lincoln December 1, 1862. Annual Message to Congress: Concluding Remarks.

CAREER ADVICE

GOV TALK